Rereading the two biographies that Aquilino Ribeiro wrote about Camões and Camilo Castelo Branco is no task for Portuguese people who barely know their own language. But they have nothing to lose by learning new words.

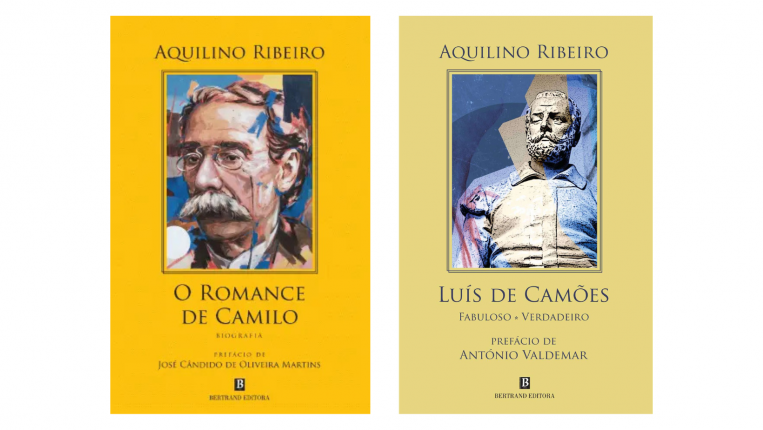

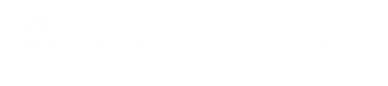

Seven decades after the publication of the biographies of Luís Camões (1950) and Camilo Castelo Branco (1957) by the writer Aquilino Ribeiro (1885-1963), Bertrand is reissuing each of them in a single volume, originally published in two and three volumes respectively. It adds two prefaces to each, by António Valdemar and José Cândido de Oliveira Martins, as well as onomastic indexes. Compared to the date of the first edition, the name Aquilino Ribeiro will mean little to most people - despite the editorial effort of continuous reissues in recent years - as it belongs to another time, even if distant from the ideals of the Estado Novo. Recognised at the time by most of his peers, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1960, his death was banned from being reported by censorship, and in 2007 he was transferred to the National Pantheon.

One does not need to read Aquilino's bibliography to understand why he is almost ignored today; after all, cultured and master of a Portuguese language that is not always understandable to the current generation of speakers, he is gradually being forgotten.

Even though major national issues remain, as noted by preface writer António Valdemar after describing the process of approval of Os Lusíadas by the Inquisition, in which the author and censor trimmed what was necessary in order for it to be authorised. According to Valdemar: ‘Living under a regime of censorship, as in the time of the Inquisition, in his view there were conversations and readjustments between the censor and the author, and thus issues such as pagan narratives and inflammatory verses of sexual exaltation, such as those in Ilha dos Amores, were overcome.’

The new edition of Luís de Camões – Fabuloso * Verdadeiro hit bookshops last year, when his birth (1524 or 1525?) was being celebrated, and Valdemar decided to make this biography more current, comparing the times and problems of the country. Here are some examples of what he considers to be an incentive to read Camões, especially Os Lusíadas, as Aquilino's work confronts us with its – and our – relevance today: "In numerous passages, we encounter a vigorous accusation of complicit silence and business promiscuity; he rebelled against the widespread corruption in Portugal, with a political class thirsty for power and unpunished, the precariousness of labour relations, and the crisis in health and justice."

Right at the beginning of his biography of Camões, Aquilino justifies his commitment to studying the poet: ‘A thorough and meticulous review is required.’ He states that he did not find any ‘new sources’ but rather details that had been misread until it was his turn. For example: ‘The three private letters that remain from the poet,’ as well as many other specific details in order to find the ‘real Camões.’ Aquilino Ribeiro includes in the afterword on the penultimate page one of the criticisms made of him after a first version, Camões, Camilo, Eça e Alguns Mais, quoting Norberto de Araújo: ‘Camões was not quite as Aquilino saw him.’

Romance de Camilo is the most recent biography to hit bookshops about the writer Camilo Castelo Branco, also by Aquilino Ribeiro, with a preface by Cândido de Oliveira Martins. Aquilino had already devoted himself to several works and essays on Camilo and, in choosing the title of this biography, the preface writer considers that it was due to a desire to demonstrate an ambiguity, as he explains in the preliminary note: ‘This book, despite its title, cannot be considered a novel, it is true history.’ It should be noted that this is not his invention, as Camilo had already behaved in this way during his lifetime and his own story was novelistic. Cândido de Oliveira Martins confirms this in his preface, concluding that "Camilo's troubled existence was a true “novel”, with no shortage of picaresque moments. The writer's troubled and scandalous life contributed greatly to this.‘ For the researcher, it was not only these qualities that shaped his future image: ’Also, to a large extent, the image or images that Camilo built of himself, insistently drawing the authorial figure, so often projected in his writing, in various autobiographical tones."

Cândido de Oliveira Martins refers to what Aquilino reveals when he addresses this legacy of Camilo in writing this biography as follows: “Seeking the man stung by genius and bladders, who until middle age spent his days in the Algarve, was the father of two crazy children, fought, confessing himself a commoner, the crown of viscount, married late to the poor matron led astray from her home, despised by women, an animal of nerves, irregular in everything.” According to the preface writer, all these biographical angles of Camilo were well known to Aquilino and sufficient to advance this bio-bibliographical project, which aimed to “demystify the portrait of Camilo, removing the hyperbolic and artificial veneer that had been stuck to him.”

Aquilino Ribeiro's two gigantic biographical efforts on Camões and Camilo were not unanimously received at the time of publication. Cândido de Oliveira Martins closes his preface by recounting the controversies generated by Camilo, and António Valdemar does the same. After all, his biography sparked much debate because, by ‘emptying the myths,’ he ‘swept away the cobwebs’ that interested the intellectuals and politicians who sought to ensure the continuity of the regime.